The Monomyth Model of Story Structure

By Glen C. Strathy

The monomyth is a model of story

structure based on the writings of Joseph Campbell, as described in his

book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

The basic premise of Campbell's work is that the vast majority of mythic tales from all of the world's cultures follow the same basic pattern. They present a universal model of a spiritual journey or psychological maturation. What makes these stories so enduring is that everyone can see themselves in the story and gain personal insight into their own lives.

Christopher Vogler wrote a summary of Campbell's book which popularized the model among screenwriters. His summary was later expanded in the book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers.

As an Amazon Associate, this site earns if

you purchase these books...

The Hero With a Thousand Faces

Since then, many screenwriters and novelists alike have used the monomyth as a basic model of story structure.

I confess, I have always resisted the lure of the monomyth (which means "one universal story) because it implies that all stories are more or less the same or at least follow the same structure with only a few variations. (Compare this to Dramatica, which allows for over 32,000 dramatically sound story structures.) However, I cannot deny that a great many highly popular stories follow the monomyth model. This is especially true for young adult stories (those written for an audience between 13 and 24 years of age). So if you are interested in writing for this age group, you may find it useful to be aware how this model works.

As with other story models, dating back to Aristotle, Campbell describes the monomyth as composed of three parts (though it works quite easily with a four-act structure, as I'll explain momentarily). Campbell's three parts are ...

- Separation or Departure (from society).

- Trials and Victories of Initiation

- Return and reintegration with society

As I mentioned, this is the formula for a spiritual journey, and the mythological stories, which Campbell drew on, are intended to convey spiritual lessons.

It's also the formula for a rite of initiation, which may be why the monomyth is so popular among young adults. It echoes the process all teenagers go through as as they transform from children into adults. Seen from this perspective, the three stages might be described as ...

- As the young teen leaves childhood, he/she moves towards greater independence from parents.

- Adolescence and the struggle to become an adult (to come to terms with adult power, shoulder adult responsibilities, become sexually active, achieve a new understanding of one's parents, find one's place in the world, establish a career, make a mark, etc.).

- Settling into adulthood (marriage, parenthood), so the cycle can continue.

Many popular young adult books describe exactly this process. They show a young teen who one day (around the onset of puberty) gains new powers and becomes aware of a much larger world in which he/she must participate without parental supervision (which is why many heroes are orphans). He or she must struggle to find allies, deal with adversaries, win a place for himself, and then settle down into an adult life of marriage and children. The Harry Potter series and The Hunger Games are just two of the most popular stories today that echo the monomyth.

So let's look more closely at how the monomyth works and how it might compare with Dramatica.

Campbell mentions seventeen typical parts of the monomyth. However, it is important to note that only some of these parts are essential to the structure. Others are options which the writer can choose among. I mention this because some depictions of the monomyth show all seventeen parts in sequence, as if they are all supposed to appear in every story, which is a misreading of Campbell. In fact, once you have selected your options, there are really only ten parts of the monomyth that are required to be in a story. (Vogler, I should note, reduces Campbell's seventeen parts to twelve by summarizing some of the options--though he also adds a stage.)

So now let's look at the parts...

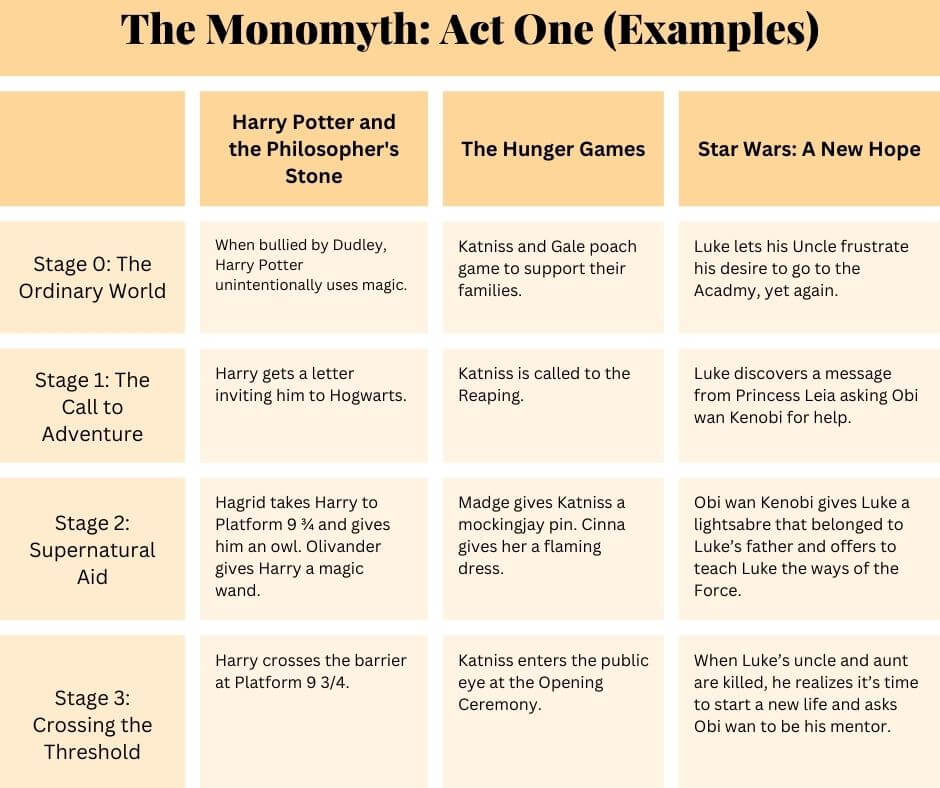

Act 1: Separation or Departure

The first part of the monomyth is concerned with the hero deciding whether or not to go on the adventure or to participate further in the story.

0. Hero Introduced in his Ordinary World

This is the stage Vogler adds to the monomyth (which is why I've numbered it "0." This stage introduces the hero (a combination of protagonist and main character) by showing who and where he is at the start of the story. In young adult books, the hero is typically on the cusp of adolescence. The word "ordinary" is a little misleading, since the best way to introduce the hero is not to show him having an ordinary day, which would be a rather dull way to begin a story, but to show him dealing with the kind of situation or problem he typically encounters in the way he typically does. This lets the reader know who this person is before the story has a chance to change him.

1. Call to Adventure

Like the first signs of puberty, the call is a messenger summoning the hero to embark on the adventure. As Campbell writes, "The familiar life horizon has been outgrown; the old concepts, ideals, and emotional patterns no longer fit; the time for the passing of a threshold is at hand." The hero is called towards a bigger world of "unimaginable torments, superhuman deeds, and impossible delight," in other words, adulthood. Sometimes the hero willingly answers the call. Other times he may be kidnapped, sent, or lured onto the path. Or he may stumble onto it by accident.

Often, it takes several "calls," each more insistent than the last, before the hero agrees to go on the journey.

1A. Refusing the Call

Sometimes, the hero flat out refuses to go on the adventure. It's an option. However, refusing to grow up and live the new life that calls has its consequences. Of such a hero Campbell writes, "All he can to is create new problems for himself and await the gradual approach of his disintegration." Often such characters end up magically frozen, comatose, or trapped in perpetual torment.

Sometimes, the hero who hides from the call or refuses its summons can be rescued by others (as in Beauty and the Beast or Sleeping Beauty). Sometimes, it also pays not to jump at the first offer of adventure that comes along but to wait for the right one. But it's also true that a few potential heroes simply blow their chance.

Note: the hero who refuses is a not to be confused with one who simply requires several calls before saying "yes." (This is an important point which some writers and theorists miss.) The refusal is an option that is rare because it usually means the end of the story, at least in regards to this character remaining the main character. From then on, the story can only continue if another hero takes over.

2. Supernatural Aid

"For those who have not refused the call, the first encounter of the hero-journey is with a protective figure," writes Campbell. It is important to note that the adolescent cannot get help from a parent, because that would mean staying in the role of a child. However, a grandparent-figure is often a different matter--caring enough to offer help and advice, but sufficiently removed to not take over the adventure. The protective figure is often an older mentor or Guardian archetype who offers advice, magic amulets, special tools, or even helpers who can watch over the hero, but still lets the hero fight his own battles. Often this is someone who has had their own adventure but is now past the age of adventuring (think Dumbledore, Hamish, or Obi wan Kenobi).

3. Crossing the First Threshold

Now the hero is ready to set foot on the path, to properly leave the comfort of home and venture into the wider world. Campbell notes that there is often some anxiety about this step. And sometimes this anxiety is expressed by having a threshold guardian who the hero must overcome, perhaps by proving himself worthy to go on the journey.

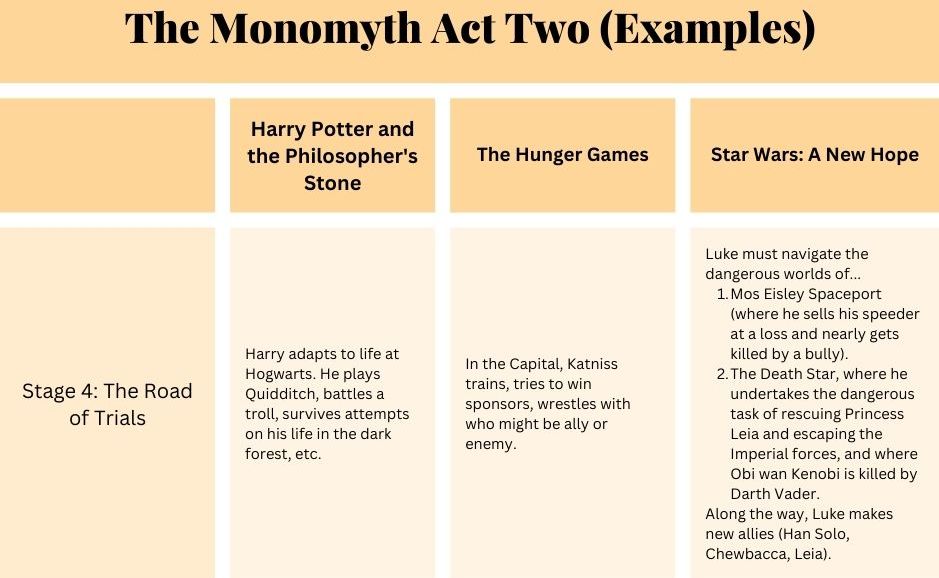

Act 2: The Trials and Victories of Initiation

4. The Road of Trials

Now that the adventure has begun. the second act of the monomyth is the complication phase. The hero traverses an unknown landscape where he must face a series of trials, challenges, and problems, aided by the advice, gifts, and agents of his Guardian. These trials can take many forms, and Campbell lists some of the most common as...

- Abduction (or imprisonment)

- Crucifixion (suffering)

- Dismemberment (losing things)

- A Wondrous Journey

Again, these are options you may choose from. Also, while in mythology these events may be presented as literal, in most stories you will create symbolic versions of them for your hero to undergo.

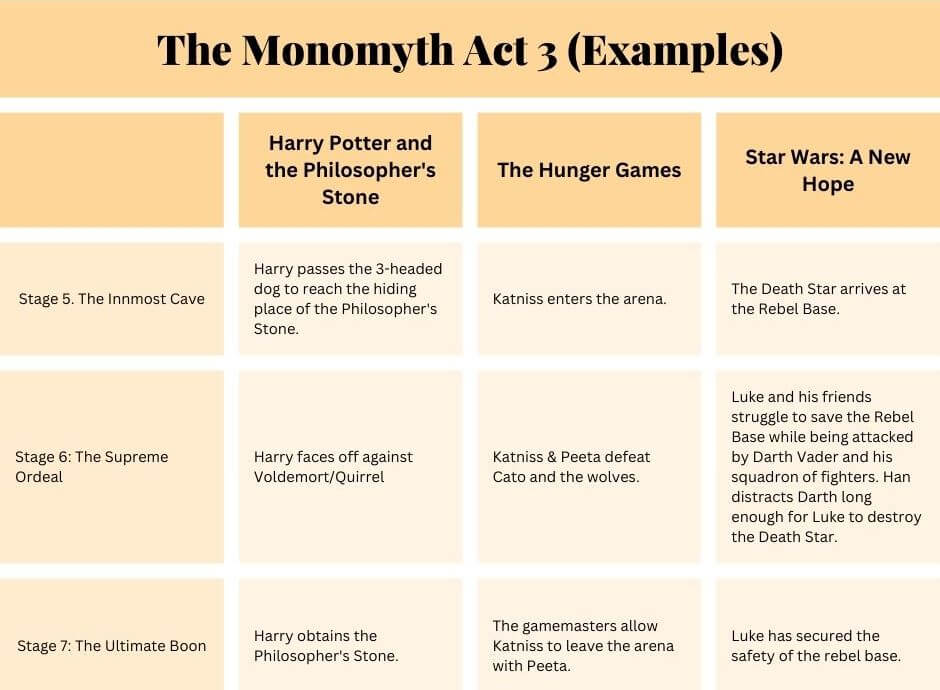

Act 3: The Hero Endures the Supreme Ordeal

This is Vogler's term for act three of the monomyth (in a four-act structure), also known as the Crisis. As with the Road of Trials, Campbell discusses several typical features of this part of the story.

5. Reaching the Innermost Cave

The biggest test the Hero faces in the monomyth takes place in a special arena which Campbell calls the "Belly of the Whale" or "Innermost Cave." This is a womb-like place from which the hero is to be reborn. In other words, the hero goes in as a child (still unproven) and comes out as an adult. The cave can appear as a tower, castle, sanctum, lair, or other stronghold.

6. The Supreme Ordeal

This final test can come in a couple of forms...

- Dragon Battle. Like the name suggests, this is a monster to be defeated.

- Brother Battle. This is a fight between the hero and his opposite who is a dark version of himself. For example, Voldemort can be seen as a dark version of Harry Potter. Darth Vader is the dark version of Luke Skywalker. Cato, the career tribute, is the opposite of Katniss. To triumph, the hero must be willing to sacrifice some aspect of himself (pride, fear, beauty, virtue, even life itself). In many myths, the hero either swallows the sibling or is swallowed, and then discovers they are the same, thus owning and triumphing over his shadow

7. The Ultimate Boon

The success of the hero's quest can be illustrated in a number of ways.

a) Getting the Prize

Having overcome his greatest adversary, the hero then has to claim his reward. And there might be one final trial to prove his worthiness to the guardians of the ultimate prize, who then bestow it upon him. One such trial might be called "Resisting Temptation." The hero may be offered a tempting prize... but it is a trap. Accepting the offer would lead to his downfall. The hero must reject the offer in order to succeed. He must be willing to "lose the world but retain his soul." For instance, in The Hunger Games, after Katniss has defeated Cato she is told she must only do one more thing to win -- kill Peeta. This would be the easy way out, but to do so would let the games turn her into a monster, something Peeta warned her about. Instead, she chooses a suicide pact with Peeta that would have her die but stay true to herself -- a move which forces the Gamemasters to repent and let her leave the arena with Peeta still alive.

On the other hand, if the guardians are unwilling to bestow the prize, the final trial may be to defeat the guardians and take the prize. Either way, the hero shows he has symbolically transitioned into adulthood and the prize is his proof, even if it is only a scar.

Other options for the Crisis include...

b) The Meeting with the Goddess

A "mystical marriage with the Queen Goddess of the World" is another option for your hero, or in the case of a heroine it may be a similar marriage with the "heavenly husband."

Of the goddess of myth, Campbell says she symbolizes the totality of the female--mother, sister, or lover. She is, "the incarnation of the promise of perfection... She encompasses the encompassing, nourishes the nourishing, and is the life of everything that lives. She is also the death of everything that dies....the totality of what can be known. The Hero comes to know."

Of course, the hero must approach the goddess properly in order to be accepted. Symbolically, he must have "the eyes of understanding...kindness and assurance."

In many popular stories, this "mystic marriage" is simply a matter of "getting the girl" or the boy. The symbolism probably comes from traditional idea that to be accepted by a lover (for men) or to marry and lose one's virginity (for women) marks entry into adulthood.

c) Rejecting the Evil Parent, Temptress, or Bad Boyfriend

For some heroes, resisting an inappropriate lover (possibly one who symbolizes an incestuous relationship) is the real ultimate ordeal. To give in to the urges of the flesh is to be an animal, whereas the ability to decline an unworthy partner is a sign of maturity. So rejecting a seductive female power-figure, perhaps in favour of an equal partnership with a more suitable woman can be the act that shows the hero has become a man.

A female heroine may similarly use this moment to finally dump the bad or abusive boyfriend. She may leave the tyrannical father-figure (sometimes incestuous) or the evil stepmother who has kept her subservient (a child) for so long. This frees her to form an adult relationship with the man who recognizes her true worth and offers her the respect and status she deserves (see above).

d) Atonement with the Father

In this variation, the hero's transition into adulthood is symbolized by having a father-figure recognize the change in him, that he is now an equal to the father. For example, when Darth Vader slices off Luke's hand in The Empire Strikes Back, it is a symbolic circumcision that shows Luke is still a child. When Luke cuts off Dark Vader's hand in The Return of the Jedi, it is more of a castration that knocks Vader down a peg and forces him to recognize that Luke is now a man. It is then that Vader asks Luke to remove his mask so he can look upon him with his own eyes -- so there are no barriers between them.

For a heroine, this is the moment when the good father-figure recognizes she is no longer a child but an adult of equal power to the mother she may be displacing.

e) Apotheosis

All of the above options represent a rebalancing of the forces in the world to accommodate the fact that the hero is transitioning from a child to an adult, just as the roles and power-structure of every healthy family must adjust as the children grow up and the parents age.

Sometimes, however, this rebalancing takes the form of the hero's ascent to a place beyond struggle, where the roles of male and female, hero and villain, friend and foe, no longer exist and where time (linear thinking) and eternity (holistic thinking) are unified.

Of course, this elevated state is not one that mortals can generally hold, any more than the moment of victory on the battlefield (when the opposing forces have been resolved) can last beyond a night of celebration. The next day, there is new work to be done, and the trick is to see what will be different as a result of the victory.

Note: Here I have imposed a 4-act structure onto the monomyth model, which works generally, but not rigidly. Star Wars has a 4-act structure and follows the monomyth, but not in the same way as the others.

Note: Here I have imposed a 4-act structure onto the monomyth model, which works generally, but not rigidly. Star Wars has a 4-act structure and follows the monomyth, but not in the same way as the others.Act 4: Return and Reintegration with Society

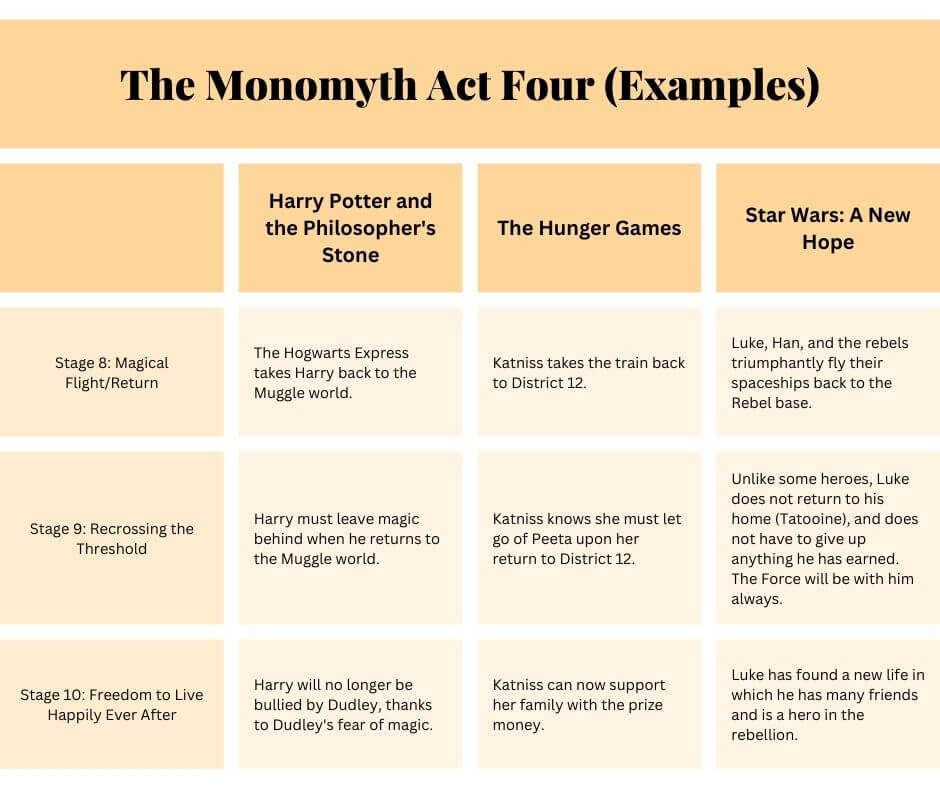

Vogler calls this fourth act of the monomyth "The Road Back." There are basically three parts to what happens after the crisis point...

8. The Road Back

a) Refusal of the Return or The World Denied

Sometimes, the hero realizes he has no interest in returning to his former life and either remains in the "cave" or other world where the crisis was resolved, or else he heads into unknown realms beyond the world we know, never to return.

b) The Magic Flight

Campbell explains this best: "If the Hero in his triumph wins the blessing of the goddess or the god and is then explicitly commissioned to return to the world with some elixir for the restoration of society, the final stage of his adventure is supported by all the powers of his supernatural patron. (On the other hand, if the trophy has been attained against the opposition of its guardian or if the hero's wish to return to the world has been resented by the gods or demons, then the last stage of the mythological round becomes a lively, often comical, pursuit."

c) Rescue from Without

Sometimes, the hero would gladly stay in the other world, but it might not be the best choice for anyone in the long run. His society may desperately need the prize he has won. They may need the new adult to take his place in the community. So they rescue him and bring him home.

In stories where the hero has journeyed into a mental, spiritual, or dream world while his physical body remained behind, the people in the real world must often pull him back to his body and back to consciousness.

9. The Second Crossing

The hero must cross the borders between the wider world and his home once more. Here, there are two options...

a) Often, the hero must give up some of the powers he has gained in order to make the transition back to ordinary life. He may only be able to take home some of what he has acquired while leaving leave behind something of value--including sometimes the lover he has won.

b) Master of Two Worlds. Sometimes the lucky hero now has a home in both worlds.

10. Freedom to Live/Return with the Elixir

Having won his place in the world, the hero may now settle down to live in the world, free of the threat or problem the adventure has resolved. The elixir he has won has cured the world of its illness and imbalance. In Dramatica, this is termed a Successful Outcome, and it is necessary for the reader to see that the journey has been worthwhile in the end. So we learn that Harry Potter marries Ginny and settles down to parent a happy family of his own, as does Katniss with Peeta--knowing of course that one day their children will head off on their own adventure into adulthood.

It is the nature of the monomyth that it favours such a happy ending. Children must become successful adults so that they might nurture the next generation, and the cycle may continue.

Vogler notes that in some comedies the hero fails to get the elixir, in which case he is doomed to repeat "the same folly that got him in trouble in the first place." But that again is another variation.

Comparing the Monomyth with Dramatica

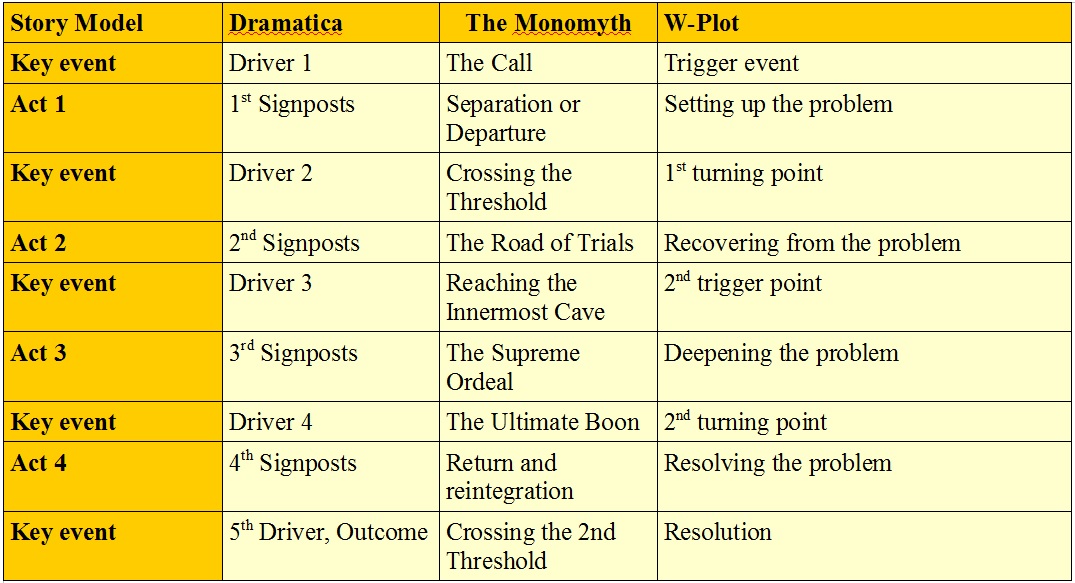

As usual, the stages of the monomyth reconcile quite easily with the Dramatica model and the W-Plot, since all these models simply use different terms to describe the same basic story structure. Also as usual, the biggest difference is that Dramatica is the only one that outlines all four throughlines (Overall, Main Character, Impact Character, and Relationship). The monomyth is primarily concerned with the Overall throughline, though somewhat informed by the Main Caracter throughline. However, if we set aside all but Dramatica's Overall throughline, we can construct a chart that illustrates the parallels...

You will note that the introduction of the Hero and "Supernatural Aid" are both part of Act 1, and not really separate stages on their own. Similarly, "Freedom to Live" is technically part of Act 4 (though it occurs after the 2nd Crossing).

Read Vogler's original memo explaining the Monomyth for screenwriters.

- Home

- Story Structure

- Monomyth