Understanding The Seven Basic Plots

By Glen C. Strathy

A comparison of Christopher Booker's theories of story with Melanie

Anne Phillips and Chris Huntley's theory of Dramatica.

(As an Amazon Associate,

this site earns if

you purchase this book

after clicking this link...)

Christopher Booker's book, The Seven Basic Plots: Why we tell stories, is an academic investigation into the nature and structure of stories. As a fan of Dramatica, which I believe is the most complete and open-ended theory of story structure, I was naturally interested in seeing how Booker's theories compared, and whether Booker offers any additional insights which may be of practical use to writers.

Because this is a lengthy work (roughly 700 pages), it may take me more than one article to discuss the theories it presents. So please consider what follows as an initial overview. I will add more detailed analyses of aspects of the book in other articles (which will link from this page) at a later date.

However, lets begin with the part of the book of most interest to writers...

The 7 (or 1, or 9, or...) Plots Themselves

As you can guess from the title, The Seven Basic Plots argues that there are seven basic plots that writers have used throughout history, and that these have certain similar structural features.

Normally, I resist approaches like this that try to reduce the universe of stories down to a handful of types. It's not that I disagree with the conclusions these approaches reach. Undeniably, good stories share many common structural features. What I dislike is how reductionist approaches tend to leave one with the impression that all stories are more or less the same. It may be useful from the perspective of literary criticism, to develop a broad understanding of how literature works and its role in human culture. But from a writer's point of view, making stories appear “all the same” makes them less interesting. Drama, excitement, and emotional engagement come from differences, from stories that seem new and unique.

Reductionist approaches also deliver the message that a writer has almost no hope of creating an original plot. That is not a particularly useful perspective for a writer who is trying to develop a new and exciting story idea.

I don't believe writers approach their craft with the desire to write the same stories over and over again, nor to write the same stories that have been written a thousand times before by other writers. One of the reasons I like Dramatica is that, while it fully describes the structure of stories, it does not limit possibilities. Following the rules of Dramatica, writers can create an almost infinite variety of stories (over 32,000 in its current form, and potentially four times as many).

Nonetheless, when you are struggling with a story, it can be helpful to look at the well-worn paths created by successful authors, because it can help you avoid most of the pitfalls you could stumble into otherwise. And, to be fair, Booker's theories are not quite as limiting as his title suggests for the following reasons...

A. Despite calling the book, The Seven Basic Plots, Booker actually identifies nine basic plots. These are...

- Overcoming the Monster: in which the hero must venture to the lair of a monster which is threatening the community, destroy it, and escape (often with a treasure).

- Rags to Riches: in which someone who seems quite commonplace or downtrodden but has the potential for greatness manages to fulfill that potential.

- The Quest: in which the hero embarks on a journey to obtain a great prize that is located far away.

- Voyage and Return: in which the hero journeys to a strange world that at first is enchanting and then so threatening the hero finds he must escape and return home to safety.

- Comedy: in which a community divided by frustration, selfishness, bitterness, confusion, lack of self-knowledge, lies, etc. must be reunited in love and harmony (often symbolized by marriage).

- Tragedy: in which a character falls from prosperity to destruction because of a fatal mistake.

- Rebirth: in which a dark power or villain traps the hero in a living death until he/she is freed by another character's loving act.

- Rebellion Against 'The One': in which the hero rebels against the all-powerful entity that controls the world until he is forced to surrender to that power.

- Mystery: In which an outsider to some horrendous event (such as a murder) tries to discover the truth of what happened.

The last two plots are only discussed late in the book because, as Booker explains, they were quite rare for most of history. Today, of course, Mystery plots have become quite popular. Rebellion Against 'The One' is still less common, but I would argue that some great science fiction stories are based on it – especially versions where the hero wins against the overwhelming power of society (e.g. The Prisoner, The Matrix).

Booker does make it clear that he has much more respect for the first seven basic plots than the last two. Nonetheless, I think it's a little snobbish to say that Mystery stories are somehow inferior to Overcoming the Monster.

B. Booker acknowledges that each of the seven basic plots comes in several variations, including dark (or less satisfying) versions, depending on which characters represent the forces of light and dark, how the story ends, the amount of realism, etc. For instance, Overcoming the Monster has a number of variations including...

- Western (town threatened by outlaws)

- Melodrama (hero threatened by scheming villain)

- Thrillers (world threatened by madman)

- War stories (world threatened by Nazis or equivalent)

- Science Fiction (world threatened by aliens or a man-made threat/monster)

- Sympathetic Monster (e.g. King Kong)

C. Booker acknowledges that many stories incorporate elements taken from more than one of the seven basic plots, allowing for additional variations. However, unlike with Dramatica, Booker does not suggest rules that would determine whether a particular combination of elements will create a satisfying story. (Rather, he seems to believe that only the “light” or archetypal versions of the seven basic plots are truly satisfying.)

The Basic Pattern to the Seven Basic Plots

Booker describes almost all of the seven basic plots in terms of five stages. In this, he echoes Aristotle, Freytag, and Shakespeare, though, like most theorists, he assigns his own set of labels to the stages.

Booker's five stages are...

- Anticipation: in which the initial setting is established and reader is introduced to the hero/heroine, who is somehow constricted or unfulfilled.

- Dream: in which the hero embarks on the road toward a possible resolution and experiences some initial success.

- Frustration: in which the hero's limitations and the strength of the forces against him become more obvious, make attaining the resolution seem increasingly difficult.

- Nightmare: in which a final ordeal takes place that determines the resolution.

- Miraculous Escape/Redemption/Achievement of the Prize or (in the case of Tragedy) the Hero's Destruction. Booker uses various terms for this stage, depending on the basic plot. But in all cases, this stage is some sort of Resolution.

For a more detailed description of Booker's seven basic plots (including the other two) click here.

Comparison to Other Story Models

Though it is tempting to say that Booker's seven basic plots follow a five-act structure, my own feeling is that this is a mistake.

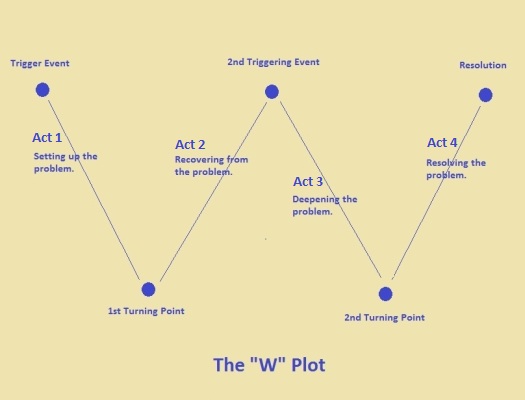

For one thing, calling it a five-act structure would make Booker's model difficult to reconcile with other story models, such as Dramatica which describes plots in terms of four acts. I've pointed out elsewhere that the W-Plot is actually a four-act structure, even though many people mistakenly call it a three-act structure. I think Booker makes a similar error. After all, each of these story models describes the same universal pattern found in successful stories. So they should all coincide.

There are two other reasons why I think Booker makes a mistake when he describes the seven basic plots in terms of a 5-stage structure.

First, Booker frequently mentions “The Call” as an important part of story structure. The Call is an event that occurs early in the story and makes the Hero aware of the possible resolution or prize and which sets the Hero on the road to achieving it. Even though Booker regards The Call as important and distinct enough to be named as a separate part of the structure, he doesn't consider it one of the stages. Instead, he attaches it to either the start or the end of the Anticipation stage, depending on which of the seven basic plots is being followed.

Second, while Booker's first four stages are described as longer sections of story which may be composed of many events, the fifth stage, the Resolution, is different. Like The Call, the Resolution is more like a single event that marks the final change in the story world (or what Dramatica would call the Outcome of the story).

So why are The Call and the Resolution single events, while the other parts are more like sequences of events? And why is one considered a stage and the other not? Here's what I think is going on...

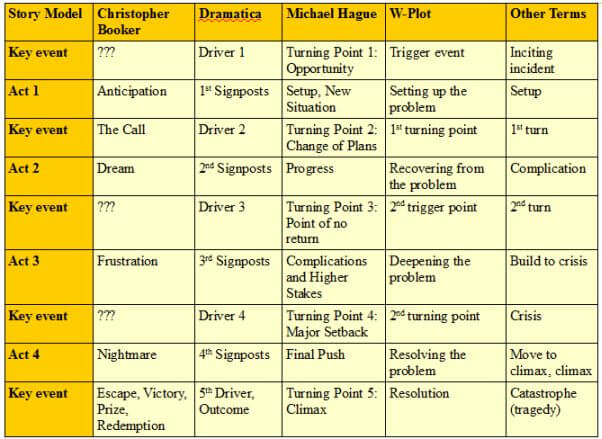

The Dramatica model and others (such as the W-Plot) divide stories into four stages. Each stage begins and ends with a key event which Dramatica calls a Driver. Other terms for these key events are Turning Points (ala Michael Hague), or Trigger Events (ala the W-Plot). Regardless the term, each of these events are changes that send the story off in a new direction (except for the final one, which marks the end of the story).

I believe that what Booker refers to as The Call is what other models call the First or Second Driver (depending on whether it comes at the beginning or end of the Anticipation stage). Similarly, Booker's fifth stage appears to be what others call the Fifth or Final Driver.

Booker doesn't refer specifically to the other three drivers, but then neither do most literary critics, probably because these drivers don't stand out as much from a reader's perspective (though they are quite important from a story writer's perspective).

In the following chart, I've tried to reconcile the terms used by Booker, Dramatica, Michael Hague, and the W-Plot users. I've also included some alternate terms for some of these stages and events. As you can see, these models all describe the same basic parts of a story, just using different words.

Based on this comparison, I think we can say that Booker's seven basic plots actually follow the same four-act structure described in Dramatica.

Story Goals

One of the core concepts in Dramatica is that all stories represent an attempt to solve a problem or rebalance an inequity. Hence, the overall throughline of every story revolves around a Story Goal (the thing the protagonist is trying to achieve that involves or affects most of the other characters). Dramatica allows for an infinite number of possible goals, grouped into 16 categories.

Separate but connected to the overall throughline is the main character throughline, in which the main character faces an inner conflict, a dilemma of whether or not to change. How this conflict is resolved determines whether the Story Goal is achieved.

Booker, on the other hand, believes there is only one universal goal of a good story: the downfall of the ego and reconnection with the true Self. Or, to put it another way, the story problem is always about an imbalance between the masculine and feminine principles. The masculine principle has become dominant to the point that it threatens the world, and the solution must be to rebalance things so that the feminine principle carries equal weight. This change must be internal as well as external. The hero (or more rarely heroine) must change – must recover and integrate the feminine part of himself. Most of Booker's basic plots end happily because this change occurs. Tragedy ends unhappily because it doesn't.

Booker argues that many variations on the seven basic plots are unsatisfying because they do not fulfill the basic goal of recovering the feminine principle. But is this really fair? Many of the stories Booker uses as examples of bad storytelling have been exceedingly popular (Star Wars, for example). Certainly, readers and audiences have found them emotionally satisfying and enjoyable. It seems rather unfair to say they are categorically unsatisfying. Should writers really abandon all variations on Booker's seven basic plots?

Let's look a little more closely at the terms feminine and masculine and see if Dramatica can shed some light on what's going on.

Feminine and Masculine Values

Booker describes masculine values as:

1) power or strength (whether physical or in terms of personality)

2) order (as in hierarchy, discipline, and justice under the law)

The feminine values, he describes as:

1) Selfless feeling

2) Intuitive understanding (“the ability to see whole, making for connection, the healing of division, and life”)

Dramatica similarly says that main characters can be either holistic (feminine) or linear (masculine) thinkers. Most male characters (and most men) are linear thinkers and most female characters (and most women) are holistic thinkers.

Where the theories differ is that, for Booker, female characters almost always embody the feminine principle and male main characters always suffer from a lack of feminine values.

Dramatica, however, is a little more flexible. It allows that some male characters are holistic thinkers, and some female characters are linear thinkers (an example would be Agents Sculley and Mulder from The X-Files). In fact, earlier versions of Dramatica assigned characters a male or female “mental sex” or brain gender, which could be opposite to their physical gender.

Dramatica gives writers more options to play with. For instance, you can create a male hero who is a holistic thinker. Such a character would hardly need to recover his feminine side to achieve the Story Goal. Rather, his success might depend on his adopting more masculine values.

On the other hand, a female heroine might be a linear thinker who can only achieve the goal by adopting more a more holistic outlook or feminine values.

(In fact, the conflict between the holistic and linear ways of thinking often play out in the relationship between the main and impact characters. If one is holistic, the other tends to be linear, and vice versa. The impact character is a concept unique to Dramatica, but Booker comes close to it when he observes that male characters are often saved by union with a female, and vice versa.)

Dramatica also allows for the possibility that main characters don't always need to change. In some stories, staying steadfast is the choice that will let the hero or heroine achieve the Story Goal. The fact that neither the hero nor the audience can be certain what the right choice is makes stories less predictable, and therefore more engaging.

Booker doesn't seem to allow for steadfast heroes.

Archetypal Characters

In addition to the seven basic plots, Booker describes a number of archetypal characters. Some of these will be familiar to everyone, such as hero and heroine. Some are similar to archetypal characters found in Dramatica. For instance, Booker's Wise Old Man and Anima characters are male and female versions of what Dramatica calls the Guardian. Similarly, Booker's Tempter and Trickster are good and evil versions of what Dramatica calls the Contagonist.

The difference I notice is that Booker interprets stories from a psychoanalytic perspective in which many characters symbolize fathers, mothers, and siblings. For this reason, many of his archetypes have definite genders associated with them.

Dramatica, on the other hand, allows any character to take on any of the archetypal roles. Unlike Booker's Wise Old Man, Dramatica's Guardian doesn't have to be old or male. The Guardian role could be played by a child, a young woman, an animal, a computer, or any other sentient being.

It may seem that I am being rather dismissive of Booker, but that would be unfair. Booker did not write The Seven Basic Plots for the benefit of writers but as a work of literary scholarship, particularly for those interested in psychoanalytic theory. Booker has obviously spent much time struggling to uncover patterns in literature, and his book provides a vast survey of the history of storytelling. There is certainly something to be learned from his description of the seven basic plots (or nine, or ...) and the archetypal characters he describes. And in future articles, I plan to examine these in more detail.

However, as a practical theory for

writers, I feel that Dramatica puts fewer limits on a writer's

imagination and allows a greater variety of dramatically sound plots

and characters. It is also more suited for today's culture, which is becoming increasingly liberated from sexual stereotypes.

For more detail on the structure of each of Booker's seven (actually nine) basic plots click here.

(As an Amazon Associate, this site earns if you purchase products after clicking these images.)

- Home

- Story Structure

- Seven Basic Plots