Syd Field's Model of Screenplay Structure

By Glen C. Strathy

As an Amazon Associate,

this site earns if

you purchase this book...

Syd Field was for decades a highly regarded screenwriting teacher.

His methods, theories, and tips on writing can be found in his popular book, Screenplay, the Foundations of Screenwriting.

Although Field's primary focus was the full-length screenplay, the principles of story structure are the same for all forms of fiction. And writers face similar challenges regardless of their medium.

Whether you want to write screenplays, novels, plays, graphic novels, or any other full-length fiction form, Field's book provides you with a high accessible model of story structure and easy to follow techniques for developing stories.

Since our focus here is on story structure models, let's take a look at the one developed by Syd Field:

In many ways, Field's model, first articulated in 1979, strikes me as a forerunner of the W-Plot and Dramatica. This should be no surprise since all story models are attempts to describe the same universal story structure.

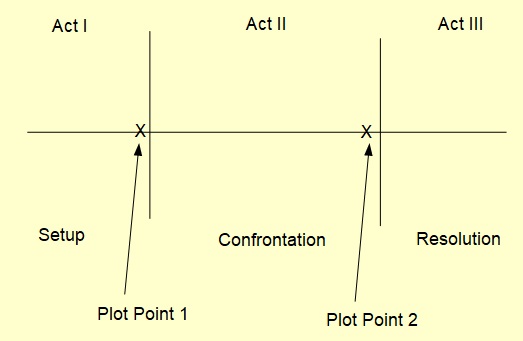

As you can see, Syd Field prefers a 3-act model, with the three acts representing the Setup, Confrontation, and Resolution. The setup, or Act 1, introduces the main character and his/her relationships, establishes the situation (setting, circumstances), and "launches the dramatic premise (what the story is about)."

The Confrontation (Act 2) shows the main character pursuing his/her objective while coping with a series of obstacles that arise. All the while, tension builds towards a crisis.

The Resolution (Act 3) shows how the solution to the main character's goal is achieved (or presumably not achieved, in the case of a tragedy).

Three Acts versus Four

In using a 3-act structure, Syd Field follows Aristotle, who first advised

us that all well structured stories have "a beginning, a middle, and an

end." However, Field is quick to point out that the middle act of a

story is generally twice as long as the other two.

Screenplays,

unlike novels, tend to have fixed lengths, due to the needs of theatres

to fit two screenings into an evening. A standard feature length

screenplay is roughly 120 pages long (with one page translating to

roughly a minute of screen time). In a 3-act model, Acts 1 and 3 are

roughly 30 pages each, and the middle act is roughly 60 pages.

If you favour a 4-act model (Setup, Complication, Crisis, and Resolution), then 120 pages divides into four acts of roughly 30 pages each.

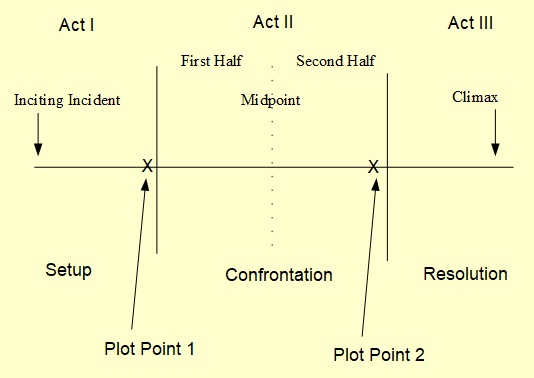

Field seems to acknowledge the validity of a 4-act structure by often treating the first and second halves of his Act 2 as separate units divided by a midpoint.

Two Major Turning Points

Field also places emphasis on two important turning points in a story, which he calls Plot Point 1 and Plot Point 2. These can be either actions or decisions, depending on the story, so long as they send the plot in a new direction.

Plot Point 1 is generally the point where the main character commits to the story goal or embarks on the journey. It's the place where many feel the story actually begins, or perhaps "finally gets started" (if you find setups dull).

Plot Point 2 is the crisis of the story. It is where it appears that all hope of success is lost, that the main character is certain to fail -- before everything reverses.

If you're familiar with Dramatica or the W-Plot models, you will recognize these Plot Points as the second and fourth drivers.

As for the other three drivers found in Dramatics (numbers 1, 3, and 5), Field acknowledges these, but uses different terms for them...

The Inciting Incident which "1) sets the story in motion and 2) grabs the attention of the reader." (This is the Initial Driver in Dramatica.)

The Midpoint, which divides the first half of Act 2 from the second half. (Driver 3 in Dramatica.)

The Ending, also known as the Climax (the 5th and Final Driver in Dramatica).

Several

people have fleshed out Syd Field's basic structure diagram to include the

other turning points/drivers, resulting in a more complete model...

Of course, Field illustrates how his model works using examples of popular films. (Two of his favourites, which it helps readers to be familiar with, are Chinatown and The Lord of the Rings.)

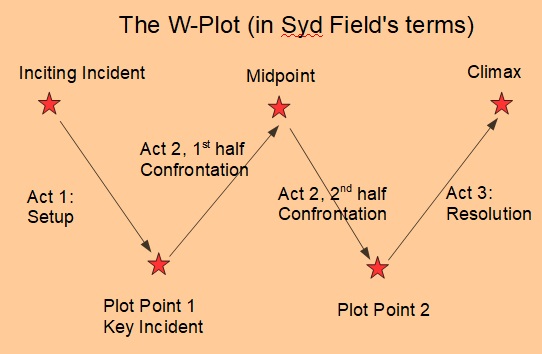

For comparison, I've translated Field's model into the W-Plot so you can easily see that both of them describe the same story structure. The only real difference, apart from what labels you prefer to use for the different parts, is whether you prefer to think in terms of three or four acts.

Choosing Your Ending First

Syd Field strongly recommends that writers should know the ending or climax of the story before they start writing, so that they know the direction the story should take.

Some writers don't do this, but I personally feel this makes a lot of sense. If you know how the story will end, you can then design your crisis to be the opposite.

For instance, if you know you want a happy ending, you should make the crisis the point where something happens that makes the situation seem hopeless -- so you can reverse it in the last act.

Or, if you have decided you want a tragic ending, the crisis should be the moment when victory seems certain, when everything seems rosy -- so you can have it all unravel in the last act.

Main Character's Journey?

You will note that Field's model is quite linear. There is no place on it for the arc of the main character's inner conflict to progress in a manner distinct but in parallel to the overall plot.

Field does, however acknowledge a lesser turning point which he calls the "Key Incident," which is personal to the main character, though he says it often coincides with Plot Point 1.

Field's definition of the Key Incident is a little vague, even though he stresses that it is important to understand what it is. Reading between the lines from his examples, Fields sees the Key Incident as an event that affects the main character personally and sets him/her on the journey. It is similar to the "Crossing the Threshold" concept from the Monomyth model. Presumably this can differ from Plot Point 1 when the latter is something that affects the story world as a whole.

More of Syd Field's Tips

Apart from his structural model, Syd Field offers a lot of other helpful writing advice.

For instance, he advocates using index cards to work out the order of plot events (something I find also very helpful). He even goes as far as to suggest an ideal number of events/scenes (14 per act in a 4-act structure). And he gives sound tips on the processes of creating characters, scenes, and sequences.

In addition to specific advice for screenwriters (such as formatting) Field offers tips on how to develop good writing routines, how to work with a co-writer, and how to deal with the kinds of self-criticism that all writers suffer from.

- Home

- Story Structure

- Syd Field