How to Create a Character Who is Believable, Memorable, and Three-Dimensional

By Glen C. Strathy

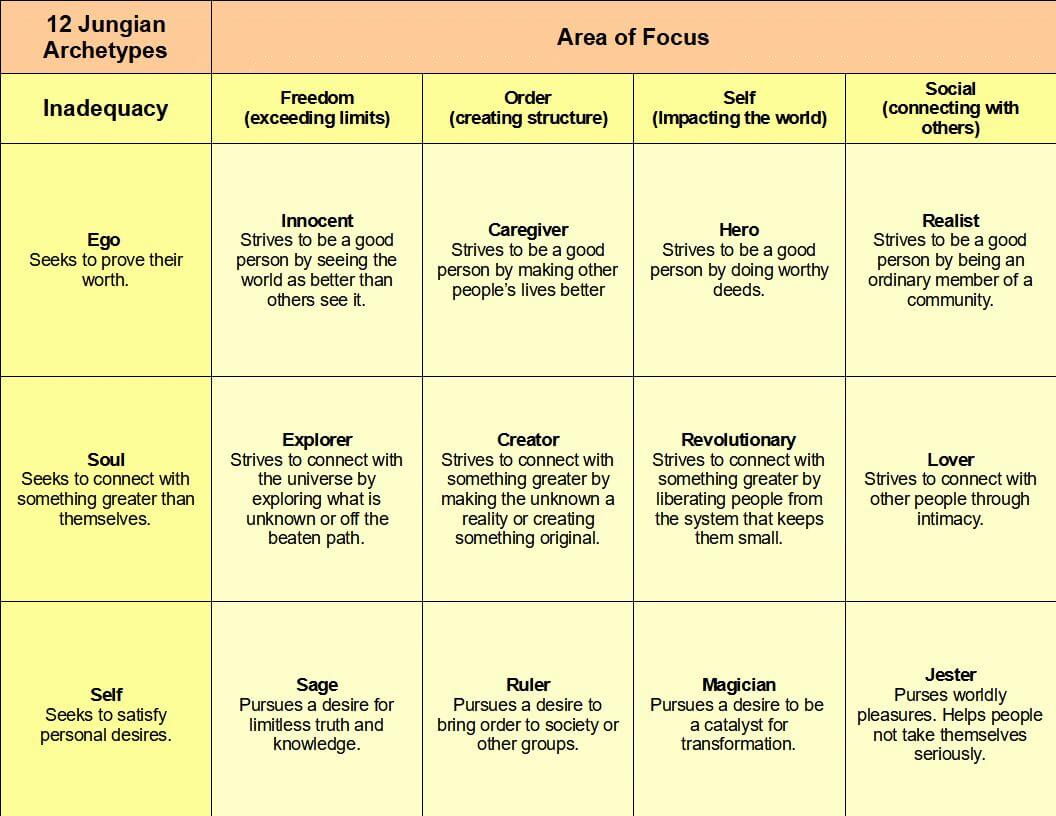

When you're learning how to create a character, you'll find there are two main approaches. Writers of plot-driven stories may start by creating characters who will fulfill the dramatic functions of the plot (see

Archetypal Characters

). They may treat the dramatic function as the character's bare bones that must be filled with layers of authentic details that work well together. The process of creating a character turns a generic character model into a specific, authentic person.

Other writers, particularly those writing character-driven stories, will start by creating characters who feel authentic, detailed, and well-rounded, and then invent a story in which these characters can take on a role. Either approach can work well.

In this article, we're going to ignore the bones (the dramatic role) of a character and focus on the flesh -- the qualities that make a character seem authentic.

Generally speaking, your challenge is how to create a character who is:

1. Memorable.

3. Believable.

4. Three-dimensional.

Of course, not every character has to meet all these criteria equally. You will develop your major characters more fully than minor ones. Some characters are only viewed externally, briefly, and from a distance. With other characters, the reader may spend a lot of time following their innermost thoughts and feelings. But let's start with external traits...

How to Create a Character Who is Memorable

The first challenge you have is how to create a character who is distinct from every other character in your novel. In fact, you must do this to keep your novel interesting. Reading a novel in which all the characters are overly similar is boring. And it can make it hard for readers to keep track of who's who. (In fact, even the writer can get confused if the characters are not distinct.) So whenever you introduce a new character, you must provide a clear impression of that character's unique traits. That way, the reader will know this is a new character, and will recognize him when he appears in later scenes.

Do your job well, and you will create characters so memorable that they stay in the readers' minds for the rest of their lives. That's not an unrealistic goal. Who could ever forget, for example, Sherlock Holmes, Ebenezer Scrooge, or Winnie-the-Pooh, after reading the books about them?

An easy way to create a character who is memorable is to give them “tags.” Tags are external traits which identify a character and set them apart from others. A tag can be any trait that can be observed by someone via the sense. For example, if you have read the Harry Potter novels (as quite a few have), you may have noticed that they contain a lot of characters. To help readers keep the characters straight, the author, J. K. Rowling, gives all her characters distinct physical tags. Here are a few examples...

Harry Potter: green eyes, lightening-shaped scar, glasses, perpetually messy hair

Hermione Granger: buck teeth, bushy hair

Ron Weasley: red hair, freckles, long nose, gangly

Rubeus Hagrid: huge, shaggy hair and beard, beetle-black eyes

Albus Dumbledore: long silver hair and beard, half-moon glasses, long fingers

Minerva McGonagall: square spectacles, green clothes, hair in bun, severe look

Severus Snape: long greasy black hair, hooked nose, sallow skin

Draco Malfoy: pale, blonde, pointed face

Vernon Dursley: beefy, no neck, big mustache

Nearly Headless Nick: ghost (so pale and translucent), head nearly but not quite severed from shoulders

I could go on.

Tags can include physical traits, clothing preferences, hairstyles, habitual mannerisms, facial expressions, speech habits, noises the character makes, or even scents - anything, in fact, that a person interacting with the character would notice about him. The combination of a character's tags should set him or her apart from all other characters in the novel. (The exception being if you want to have members of a family resemble each other.) The other exception would be if you want to confuse two characters' identities for a specific reason (e.g. you're writing a mystery and you want two suspects to be mistaken for each other).

When you first introduce a character, you include some of his or her tags in a description of his appearance or actions. Your description can be very brief. All you need to do is help your readers create an image of that character in their minds. Throughout the novel, mention a character's tags whenever the character reappears and you feel the reader needs to be reminded who he or she is.

You don't need too many tags per character – one or two can be enough for minor characters. Major characters may need more because they appear more frequently and for longer stretches. (The more time readers spend with a character, the more details they expect to learn about him or her.) So you may not introduce some tags until later in the novel.

As the story progresses, the characters will become more fixed in the reader's mind, and you may find you don't need to insert the tags as often.

Of course, the most common character tag is not a sense impression at all, yet it is the one tag you are most likely to use every time a character appears. It is the character's name.

How to Create a Character Name

Here are a few tips on how to choose names for your characters ...

1. Try to create character names that sound different from each other. Have them start with different letters of the alphabet. Avoid giving characters the same name. Of course, there are exceptions. You might want a father and son to have the same name -- because that may tell the reader something about the father's personality, or customs in that community. But then you may need to use other tags distinguish them from each other.

2. Keep character names consistent. Don't don't let your narrator call the same character “Bob,” “Robert,” “Bobby,” “Rob,” and “Robby” at different times, because your reader could think you're referring to five different people. Even if his mother calls him “Robert” and his girlfriend calls him “Bob,” your narrator must always use the same name.

3. You may want to choose character names that convey something about each character, such as his or her ethnic background. The internet is a great tool to help you do this. For instance, you can search for surnames that are Irish, Japanese, or whatever nationality fits your character. When looking for first names, many “baby names” websites will list given names by ethnic origin.

4. Many writers give characters names that say something about their characters' personalities. Again, “baby names” websites will tell you what various first names mean, so you can choose ones that fit your characters. Charles Dickens used to create character names that were quite ironic, for example: Mr. Bumble, Master Bates, M'Choakumchild (an unpleasant teacher), Mr. Sowerberry, Mr. Skimpole (who is miserly), and Mr. Headstone (who attempts murder). Other times, he used onomatopoeia, to create character names whose sound conveyed an impression of the person. For example a name like “Scrooge” certainly sounds appropriate for the “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner” that he is.

5. Alternatively, you may prefer to choose names randomly, perhaps by flipping through a telephone book. If you google “random names” you will find there are many sites that offer random name generators – including some that generate original names for fantasy characters. It's probably not good to take names directly from these sites but they are a great source of ideas. You can easily alter the results to create character names that suit your novel (for instance, you should probably change fantasy names a little so that all your characters who belong to the same culture have names that sound like they come from that culture).

It's a good idea to create a text file or a character sheet where you record all the details about each character, so you can refer to it while you're writing your novel. This can be a big help when you're on chapter 16 and you can't remember whether you made a character's eyes aqua or turquoise early in the novel.

One more tip...

Try hunting for photographs of people who look like the characters you want for your novel. You can find these in magazines or even in the catalogs of modeling agency websites. (Just remember that few people in real life are as airbrushed and skinny as those in advertisements.) You can then paste these photos into your character files.

How to Create a Character Who is Believable

Often the most memorable characters are those with highly unusual tags. However, in your determination to create characters that are memorable, you may create characters that seem far-fetched. For instance, suppose you are writing a novel that takes place in 19th century London, and you have chosen to create a character who is a female cab driver with three hands who reads Plato, wears a grass skirt, and clucks like a chicken every few minutes. Obviously, you need to learn how to create a character who feels authentic.

Much depends on how realistic your novel will be. A fantasy novel may be stuffed with characters who are strange and outlandish. And even in a contemporary, mainstream novel, there's no need to create characters who seem ordinary. Human beings are a pretty diverse species. There has ever been such a thing as a “normal” or “average” person. In every city, in every era, you find people of extremely diverse cultures, philosophies, personalities, and physical shapes – and with personal histories and backgrounds unique to them.

As for our three-handed cab driver, you may need to give the reader some explanation of why she is who she is and how she ended up in her present career – but with a little imagination, you should be able to invent a background for her that makes sense, even in an otherwise realistic setting.

The secret of how to create a character who is believable is not to make them ordinary, but to make them consistent. Readers want to believe in your story. They like to imagine it could be true, even if it seems unusual. And one sign of a true story is that it doesn't contradict itself. Even if you create characters who are unlike any human being who ever existed, the reader will accept them, provided they behave in a manner consistent with the traits you have given them and the background you have invented.

Readers can accept whatever reality you devise, so long as you play fair and don't change it arbitrarily. Your cab driver cannot, without explanation, suddenly be illiterate, or have two hands, or lose her job for wearing the grass skirt she has worn every day for five years (as if no one would have noticed it before).

To take a better example, let's suppose you create a character who is a feeble, old man who uses a walker. If, at the climax of your novel, this man gets into a fight with a gang of hoodlums and beats them to a pulp, the reader will feel you have broken the rules – you have contradicted what you previously stated about the character, and lessened the reality of the story.

But what if you really want the old man to surprise every one with his fighting skills?

The way to handle it is to make sure your story has a consistent reality, even if you don't reveal it right away. For instance, you can drop little hints early in the novel that the old man, despite appearances, has exceptional physical abilities. Perhaps he catches a baseball just before it hits a window, or leaps into a tree to rescue a cat (when no one is looking). These events may seem strange at the time, but the reader will suspend his disbelief in the hope that all will be explained in the end. After your old man takes on the hoodlums, you can reveal that he was once a champion martial artist who has chosen to hide his talents from the world. With that explanation, the reader will see that you were being consistent all along.

Some characters are just part of the setting.

Another challenge you may face is how to create a character whose only function is to be part of the setting -- and to make the world of the story seem real.

For instance, if your main character goes to a restaurant, you may have a waiter or maitre d' make a brief appearance. If your main character goes to a store, a salesclerk may pop up. These minor characters may be unimportant in terms of your plot, but you them because it makes sense for them to be there. Their presence helps reinforce the reality of the world your novel takes place in.

If you are setting your novel in the 19th century, in a small fishing town in Newfoundland, the reader will be very surprised not to see at least one male character who fishes for a living. In fact, there will probably be more than one. It would also make sense for you to create characters such as the fishermen's wives, children, and other relatives living in the same town. A little research will reveal other characters who the reader expect to find in such a town at that time – tradesman, merchants, professionals, a priest, etc. You might learn something about the ethnic background of Newfoundlanders at the time. Your town could have been settled primarily by Irish, French, or American immigrants – or a combination. You can discover what clothes people wore in that setting, what their religious beliefs tended to be, what medical services were like (to know how likely is was for people to have amputations, eyeglasses, TB or polio.).

On the other hand, if you want your novel to take place on the planet Xenofrix in the Andromeda galaxy, then you need to think about characters that might logically appear in that environment. You may have to design a world, a culture, a community, and a species of intelligent life that make sense.

Of course, sometimes you may simply mention that your main character “took a cab to the airport.” Maybe the plot needs to move quickly at that pointl, and nothing meaningful is going to happen in the cab anyway. On the other hand, if something important is going to happen during that cab ride – if your main character will have a revelation or make an important decision, etc. -- you may want to describe the cab ride in more detail. In that case, creating a cab driver may add to the realism of the scene.

Such a minor character, sometimes called asupernumerary, walk-on, spear-carrier, or red shirt (if you're a Star Trek fan), may not have a dramatic function. They may not be memorable, and they certainly won't be three-dimensional. But they do need to be believable. Your challenge remains how to create a character whose appearance, speech, and mannerisms are consistent with that setting. If not, they may call too much attention to themselves and make the setting less believable. For instance, if our three-handed cab driver is a mere walk-on, who serves no purpose in the story, her presence might be an unnecessary distraction that undermines the believability of the novel.

It is nonetheless worthwhile giving tags even to your background characters, because specific details always makes them seem more real than a generalized description.

Even better, try to create characters in the background who are consistent with your Story Goal. For instance, in the film, Casablanca, the Story Goal is for Victor Lazlo to escape the city of Casablanca and get to the free world. Most of the minor characters are also people who are either trying to escape or helping others escape.

In the film, Star Wars, the background characters on the “good” side are extremely diverse. They include numerous alien species, robots, and everything in between. The bad guys, on the other hand, are mostly homogeneous. The storm troopers are identical clones, and the Imperial fleet officers are all Caucasian men with similar accents and uniforms. In other words, the good guys accept and embrace differences, while the bad guys reject them. The background characters help illustrate that defeating the Empire will give people the freedom to be individuals.

In the novel, Bridget Jones, Bridget is a single woman wishing she could find true love. So it is fitting that her world is peopled by characters who are similarly wrestling with the challenges of either staying a "singleton" or taking a chance on romance.

Whatever the goal or message of your story, one way to convey it is to create characters, even minor ones, who are involved in that goal.

I recommend you take a little time to create characters who would make sense in your chosen setting, and a brief description of each. Again, use a separate page or file for each. Some of these you may never use. Others may become supernumeraries. Still others may evolve into more important characters as your novel writing progresses.

How to Create a Character Who is Three-Dimensional

So far, we have looked at how to create a character who is are distinct and consistent. But to give them the enough authenticity to make them engeging for your reader, we must proceed to a deeper level.

In addition to motivations or functions, Dramatica theory provides three other aspects to a character's personality to consider. When you create a character, especially a major character, it is worth taking the time to develop these aspects. In your character files, try writing a paragraph that addresses each of the following...

1. Purposes. What things does your character want to have or achieve? These can be long-term goals or present needs, and varying degrees of importance.

2. Methods.

When faced with a problem, how does your character try to solve it? How does he act? What does he do? What actions would be "in his wheelhouse" or "outside his comfort zone"?

3. Evaluations.

How does your character judge things, people, situations, herself? How

does she decide whether she is making progress towards her goals, or

whether things are getting worse? What are his opinions and beliefs?

As you answer these questions for a particular character, also ask yourself why the character is the way he/she is. Why does she want what she wants? Why does he approach a problem that way? What makes him/her see the world with that particular bias? What events occurred in your characters lives to make them the way they are? You don't need to create a complete history for a character (although a little background may prove useful at some point in your writing), but having some explanations can inform your writing and make the characters more real to you – and consequently to the readers.

The final step is to create characters who will fulfill the two most important roles in your novel. (It may surprise you to learn that these are not necessarily your hero and villain.)

- Home

- Write a Novel

- Creating Characters

- How to Create Characters