Creating Archetypal Characters Using Dramatica* Theory

By Glen C. Strathy

The process of creating archetypal characters who perform specific dramatic functions in your novel is the least understood aspect of characterization. Fortunately, it is also an area where Dramatica Theory offers the most profound help.

It is important that each of your major characters fulfills an important dramatic function -- a function that is common and vital to most stories. One reason writers sometimes feel reluctant to use character archetypes is that they are afraid of seeming unoriginal. This fear is groundless, for reasons we will cover momentarily. In fact, making sure all the dramatic functions are included in your novel can enrich it greatly.

Many writers don't understand the importance of dramatic functions, or the usefulness of archetypal characters. One reason is that every novelist has a slightly different schedule for creating characters. Some writers start the novel writing process by inventing a group of characters whom they find interesting. Then they imagine putting those characters into situations or confronting them with problems that will force them to act and interact. Out of this action and interaction a plot will eventually emerge. The characters will, in a sense, “choose their roles themselves.” (Of course, quite often these roles end up being those typically performed by archetypal characters.) Nonetheless, this method can produce characters that are wonderfully original.

Of course, the downside is that you can grow very attached to your characters before your plot has gelled. Consequently, you may be reluctant to cut characters that need to be cut when you discover they serve no essential function in your plot – or fail to include characters that fulfill necessary dramatic roles.

Other writers start with a topic or issue they want to explore. They may choose a premise – a thematic message or moral they want their novel to deliver. Then they create characters who can illustrate different points of view, experiences, or attitudes related to the topic.

If you use either of these methods, you may not choose a main character or Story Goal until fairly late in the development process. As a result, you may not have a clear sense of how your characters function in the story for some time. In fact, many writers ( pantsers especially) don't take the time to understand how their characters function until after they've written their first draft, if at all. This approach can lead to manuscripts that require much revision.

We think you can save yourself a lot of time by working out character functions early on. The approach we took when creating plot summaries was to start with an Idea for a novel plot that revolves around one character in particular – who will be the main character – and the particular Story Problem he or she is faced with.

If you are following this method, you will find that the process of developing a simple Plot Outline will automatically suggest other characters who are needed to make the story work. In other words, from the very outset you will be creating characters who fulfill important dramatic functions.

Here's how this approach works ...

Archetypal Characters and the

Dramatic Functions They Perform

Let's take a very well-worn but effective story idea mentioned in an earlier article:

“An orphaned boy is raised in the care of a powerless uncle, but watched over by an aged but powerful wizard/warrior. When the boy reaches a certain age, the old wizard tells the boy about his true heritage and helps him develop his powers until he is able to avenge his father’s death.”

(To repeat, this is the basic story idea behind Star Wars, Harry Potter, Eragon, King Arthur, and many other popular stories.)

In this brief summary, there are a number of archetypal characters mentioned or implied already:

An orphaned boy.

A powerless uncle.

An old but powerful wizard/warrior.

A villain who killed the boy's father.

We also know that the Story Goal is revenge.

We mentioned in earlier articles that the entire plot of a novel hangs on the Story Goal. Here's another profound secret: the Story Goal is also the central organizing element for character functions.

For instance, if the goal is revenge, it stands to reason that there must be a character to pursue that revenge – the orphan boy, in this case. To create dramatic tension, there must also be a character who wishes to prevent the boy from getting revenge. Naturally, the villain fulfills this role. So these two characters are in dramatic opposition. One pursues the goal, one tries to prevent the goal from being attained. The conflict between them creates drama in the story.

Of course, every writer knows that good stories generally involve a struggle between a protagonist and an antagonist, a hero and a villain. They are the two archetypal characters readers expect to see and recognize immediately. What is less widely appreciated is that, for a story to be fully developed, other dramatic oppositions must also be present which are often expressed through other archetypal characters. For example, the aged wizard and the powerless uncle also have important functions. The wizard's role is to help the orphan boy prepare himself to get revenge, while the uncle's role is to hinder him. Because these characters function in opposition, they create another important type of dramatic tension.

(For example, in Star Wars, Obi Wan Kenobi helps Luke Skywalker develop his powers and invites him to go on the quest to rescue the Princess. On the other hand, Luke's Uncle Owen pooh-poohs Obi Wan and tries to convince Luke to stay at home. Similarly, in Harry Potter, the wizard, Dumbledore, helps Harry prepare to get revenge on Voldemort, while Harry's Uncle Vernon tries to suppress Harry's abilities and often tries to keep him isolated from the magical world.)

And there are other opposing character functions that are part of a well-rounded story. Altogether, Dramatica Theory identifies 16 basic character functions, divided into 8 basic opposing pairs. (Actually, Dramatica uses the term “motivations,” but I find the term “functions” makes more sense in some cases.) In other words, to make your novel feel complete, it should include a character who...

- PURSUEs the goal and ...

- one who AVOIDs the goal.

- one who HELPs someone's efforts and ...

- one who HINDERs someone's efforts.

- one who tries to get someone to CONSIDER a course of action and ...

- one who tries to get someone to RECONSIDER a course of action.

- one who seeks a course or explanation that is LOGICally satisfying and ...

- one who seeks a course or explanation that FEELs emotionally fulfilling.

- one who exhibits self-CONTROL (focuses on one task or area to the exclusion of everything else) and...

- one who appears UNCONTROLled (tries to juggle or reacts to many things at once).

- one who makes an appeal to CONSCIENCE and ...

- one who makes an appeal to TEMPTATION.

- one who SUPPORTs (speaks in favour of) any effort and ...

- one who OPPOSEs (speaks out against) any effort.

- one who expresses FAITH (confidence something is true, despite lack of proof) and ...

- one who expresses DISBELIEF (confidence something is false, despite lack of proof).

The plot of your novel will be more fully developed if you have characters to perform each of these 16 functions. For instance, if you have someone whose role is to HELP the protagonist, see if there is a way to include another character who can HINDER. If you have a character who tries to get your hero to look at a problem LOGICally, perhaps you can have another character who will make an opposite appeal to emotion (FEELING). In other words, use your imagination to come up with ways of including as many of the 16 functions as possible.

This is not to say that you must have 16 characters in your novel. Heaven forbid you should be that formulaic! Any character in a novel can fulfil one or several of these functions, and you are free to assign these functions to different characters any way you like. You can have as few as two characters, each of which takes on half the functions. Or you can have as many as 200 characters. (Though not every one of 200 characters may perform a dramatic function in the main plot, minor characters may play important dramatic functions in subplots.) There are, however, two guidelines:

- Each function should only be fulfilled by one character at a time. Two characters serving the same function simultaneously is redundant. For instance, only one character in a scene should make an appeal to LOGIC or express FAITH.

- No character should fulfil both functions of an opposing pair. The orphan boy, for example, cannot both pursue revenge and seek to prevent it at the same time.

(I know what you're thinking. What if your protagonist is conflicted within himself? Couldn't he both PURSUE and AVOID at the same time? The simple answer is no. However, what writers often do in such situations is create two characters, both of which exist within someone's mind, who can take on opposing functions. For example, many TV shows have scenes in which a tiny imaginary angel (CONSCIENCE) and devil (TEMPTATION) sit on opposite shoulders of the protagonist, each trying to convince him to take a different course of action. Or you can create one character that represents someone's LOGICal side and another that represents their FEELing side and have them battle it out in the person's imagination.

There are also many stories, such as George Bernard Shaw's play, Man and Superman, in which multiple characters, each of which represents a different facet of one person's mind, appear in a dream or some representation of the person's subconscious where they can express their respective functions.)

Grouping Functions into Archetypal Characters

So, archetypal characters are simply classical (or stereotypical) ways writers group dramatic functions and assign them to characters. Dramatica Theory identifies 8 Archetypal Characters that represent traditional clusters of functions. As I mentioned, the two opposing archetypal characters everyone is familiar with are the ...

Protagonist (pursue, consider) vs. Antagonist (avoid, reconsider)

A protagonist considers the importance of fulfilling the Story Goal and pursues it, while the Antagonist tries to get him to reconsider and does everything to avoid the goal being achieved.

The powerless uncle and the elderly wizard are examples of two other archetypal characters ...

Guardian (help, conscience) vs. Contagonist (hinder, temptation)

The typical Guardian is like the protagonist's wise teacher, mentor, or parent who helps him and guides him into doing what is right. The Contagonist (a term invented by Chris Huntley) delays the protagonist and tempts him to give up his pursuit of the goal. (This archetypal character is sometimes known as a Trickster or Temptress.)

If you are a fan of fantasy and science fiction, you are probably quite familiar with the next two archetypal characters...

Reason (logic, control) vs. Emotion (feeling, uncontrolled)

For instance, in the various Star Trek television series, the Captain typically has two advisors. One is a Reason character (e.g. Spock, T'Pol, Data, Odo, Seven of Nine) who takes a logical approach and appears in control of his emotions. The other is an Emotion character (Dr. McCoy, Riker, Ensign Ro, B'Elanna Torres, Major Kira, Trip) who appeals to the Captain's feelings and tries to get the Captain to pay attention to more than just the main goal of the mission.

Another example is the characters Ron and Hermione from the Harry Potter novels. Ron generally fulfills the functions of the Emotion archetype, while Hermione takes the Reason functions. (Although, there are issues on which they trade places.)

If you're not a fantasy fan, you may recall that in several of Jane Austen's novels, married couples take on the archetypal characters of Reason and Emotion. For instance, in Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth's father is always rational and controlled while her mother is prone to emotional and irrational outbursts.

The final two archetypal characters are the ...

Sidekick (support, faith) vs. Skeptic (oppose, disbelief)

Sidekicks express unflinching the emotional support and faith of a best friend or pet (in some stories, the hero's dog is actually his sidekick). They approve of the hero's every plan, and are always certain it will succeed. Skeptics, on the other hand, are perpetually pessimistic and opposed to every plan. Marvin, the chronically depressed robot from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, is a good example of a skeptic.

You can use these archetypes in your own novels, particularly if you are writing genre fiction or any work which is more plot-oriented. They are a convenient shortcut, which will not appear stereotyped as long as you dress them up in new clothes.

For example, you might expect a parent to play the Guardian role, but there's no reason why you can't assign that role to a child instead. You might expect to see a female Contagonist luring the hero away from his mission with promises of a sexual encounter, or a male Contagonist tempting the hero astray with a monetary bribe, but there are plenty of other temptations your Contagonist can waylay other characters with. Besides, oddly enough, readers don't seem to get tired of the classic ways, as long as they are written honestly and freshly.

Remember too that you can create non-archetypal characters by swapping some of the functions around. Why not, for instance have one character who Hinders and uses Logic while another one displays emotional Control while Tempting others off the path? As long as you follow the two guidelines above, you are free to assign functions as you see fit. Dividing up dramatic functions in unusual ways is a good tactic in a more character-driven novel, where archetypal characters might seem too predictable.

Putting Archetypal Characters to Good Use

Let's take another example. In an earlier article, we developed part of a plot summary for a novel that went like this ...

“A female executive in her late 30s has been married to her job. But she has a wake-up call when her elderly, spinster aunt dies alone and neglected. The executive decides that she needs to have a family before she suffers the same fate. So she buys a new wardrobe and signs on with a dating service. Her boss offers her a promotion that would involve a lot of travel, but she turns it down, so that she will have time to meet some men. She goes on several dates. But each one ends in disaster. On top of that, because the agency arranges all her dates for Friday nights, she ends up arriving tired and late for the company's mandatory early Saturday morning meetings. Along the way, however, she starts to realize how the company's policies are very unfair to people with families or social lives outside work, and she begins to develop compassion for some of her co-workers that leads to improved relationships in the office.”

Assuming we are content to use archetypal characters, let's consider which of the characters mentioned in the synopsis might fill the various roles:

The female executive: obviously, she will be our Protagonist.

The spinster aunt: possibly the Guardian – she could help by leaving the executive something helpful in her will, along with a letter urging her to have a family and a life outside work.

The boss: Since he tempts the executive away from her goal of finding a husband, he is a prime candidate for the Contagonist.

Now we can flesh out the story further by adding in the other archetypal characters...

Antagonist: this could be the company itself, whose policies seem aimed at preventing the goal from being attained. We could create a company President who can embody a philosophy that is antagonistic to family life.

Reason and Emotion: Perhaps we could make two of the men our executive dates fill these functions. One could make a marriage proposal based totally on logic, but be someone she has no real affection for. The other man could appeal strictly to her emotions, but offend her rational side. Hence, neither one would fully appeal to her.

Skeptic: this could be our executive's best friend at work, who pooh-poohs her plan to look for a husband.

Sidekick: I rather like the idea that the man she eventually marries is someone who has been in her life all along but whom she has overlooked. So we could create a supportive, faithful male friend who has secretly been in love with her for years.

This example is simple, but it illustrates our point. Whether you choose to use archetypal characters, or assign dramatic functions in ways all your own, by incorporating all the dramatic functions, you will create oppositions and tensions in your novel that will heighten the drama, and hence the reader's emotional involvement.

That said ... dramatic functions are only one aspect of characterization. The next article will show you

how to make archetypal characters believable, memorable, and original.

*Based on Dramatica theory created by Melanie Anne Phillips and Chris Huntley.

- Home

- Write a Novel

- Creating Characters

- Archetypal Characters

Bonus Tip: there are numerous other systems that delineate character types, usually based on either stock characters (whose traits can trace their lineage back through many stories by other writers) or theories of personality rather than dramatic function.

The TV Tropes website lists a number of stock characters.

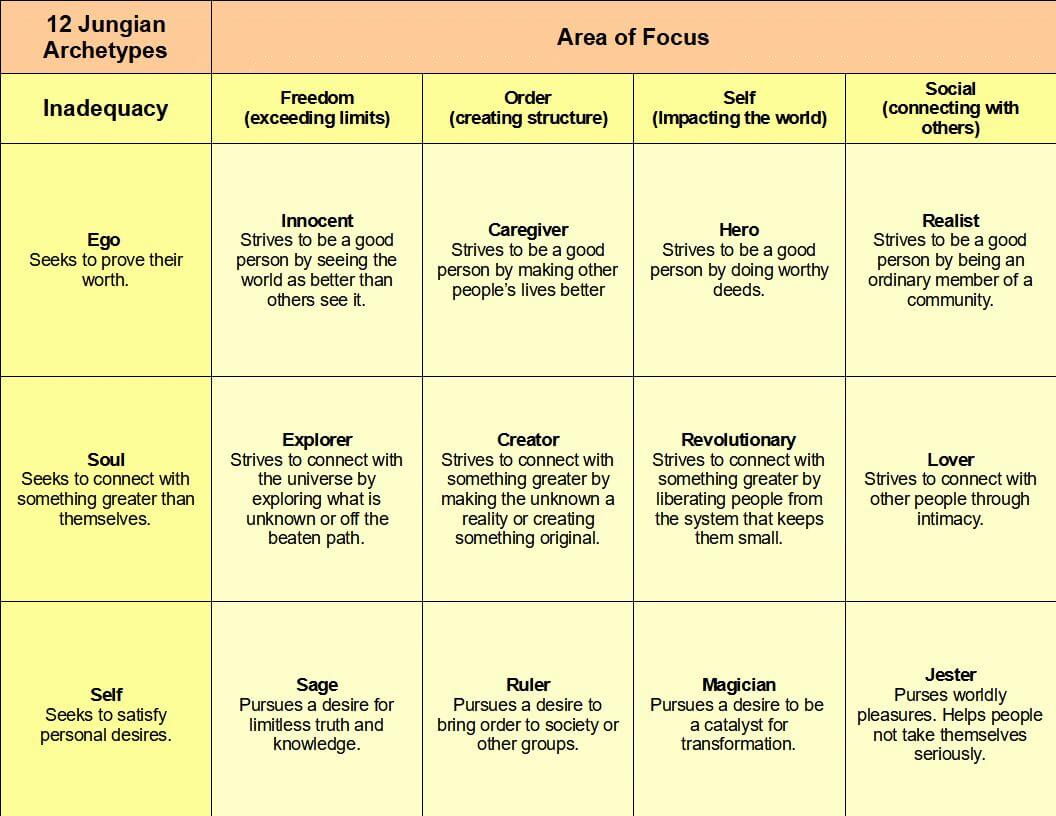

As for theories of personality, many writers have appreciated that created by the psychologist Carl Jung. Many of his personality types can be combined with Dramatica's archetypal character functions to create a wider variety of types. Click here for information on Jung's 12 archetypal personalities.

Do you have a question about archetypal characters or any other aspects of novel writing? If so, visit our Questions About Novel Writing page to get the answers you need.