How to Write Fight Scenes

By Glen C. Strathy

If you want to know how to write fight scenes that readers will love, you must understand something that may seem hard to believe at first.

Fighting, in itself, is boring.

What makes a fight scene interesting is not the actual exchange of blows or bullets. It is the context of the fight. It's the story, the stakes, the surprises, the reversals, the thematic argument (i.e. good vs. evil), the testing of a character's resolve. Most importantly, it is how the outcome of the fight will affect the characters and the story world.

The world of professional sports recognizes this, which is why commentators are so important in that form of entertainment. The commentators convey the story to the fans, helping them to get excited about the drama that is unfolding -- and anxious about how it will end.

This is particularly true in

the sport of wrestling, where the combatants assume larger than life personas and must be interviewed "in

character" before and after bouts. All this drama is designed to whip up spectators' emotions.

Similarly, one secret of how to write fight scenes is to remember that story is everything. If the fight is set within the context of a dramatically charged event, even a little thumb war can be exciting. But if there's no drama, even a huge interstellar war will be dull.

Of course, the way to make a story dramatic, whether on the scale of an entire novel or a single scene, is structure. So let's look at how to write fight scenes with a solid dramatic structure.

Before We Discuss How to Write Fight Scenes...

If you haven't read the article on writing action scenes, you should start there. I'm going to assume you already have worked out...

- How the fight scene fits into your story.

- Where it will take place.

- Who the combatants are (including their abilities).

- Who the reader should be rooting for, and who will win.

Also, note that what I am about to say about structure applies equally to other types of actions scenes (chases, races, sports competitions, etc.), or to battles involving opposing teams of fighters.

Formal vs. Informal Fight Scenes

First, we should note that some fight scenes need to be more elaborate than others. The more important a fight is to the story as a whole, the more elaborate it needs to be.

Sometimes it's okay to have a brief bit of violence, such as knocking out a guard as part of a prison escape sequence. In that case, a single blow described in one sentence may be all you need.

On the other hand, sometimes you need to know how to write fight scenes that are more significant. If your entire story has been building toward a showdown between your hero and villain that will be the climax of the novel, that fight scene should be more detailed and substantial. The readers will be eagerly looking forward to this confrontation and have a lot of emotional investment in how it unfolds. They don't want it to end too quickly; they want to savor each blow. And you don't disappoint them.

So let's first look at how to write fight scenes elaborate enough to be the crisis or climax of your novel.

How to Write Fight Scenes That Are Formal

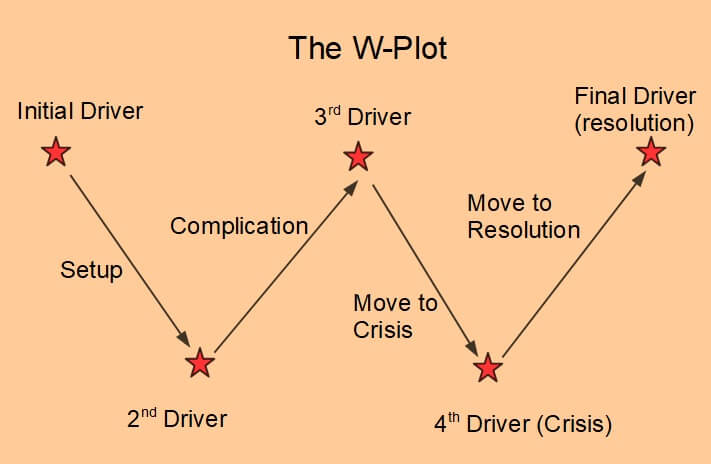

The basic map of a dramatic arc is the W-plot. You'll notice the map consists of four stages (setup, complication, a move to crisis, and a move to resolution). The beginning and end of each part is marked by a turning point called a driver.

While we usually use the W-plot to describe a story as a whole, it can also be used to structure individual scenes or events.

The W-plot illustrates some important principles about how to write fight scenes:

- The tension in the scene should build to a crisis (a major turning point), which is then followed by a resolution.

- Having four different stages makes the scene more interesting.

- The turning points help you to create an emotional roller coaster for the reader.

In other words, you shouldn't write fight scenes in which two people just keep hitting each other in much the same way until one gives up or falls down. There have to be twists and turns in the action. The nature and intensity of the fight should change several times.

Okay, so here's what each of these nine parts (five drivers, four stages) look like in a fight scene...

1. Initial Driver

Typically, this is where the challenge to the fight is made and accepted. This can be a formal challenge (as in an aristocratic duel that starts with one party throwing down a glove), or the combatants may simply have a moment of understanding when they realize a fight is inevitable.

2. Setup

The combatants prepare for the fight. Depending on the venue, time period, and style of fighting, this might involve clearing space, removing unnecessary clothing, checking weapons, or warming up.

Usually this is a good place for the main character to assess the terrain and look for anything he could use to advantage.

The combatants might begin by circling each other for a while, or delivering a few fake blows in order to assess each other's level of skill and decide on the best strategy of attack.

3. Second Driver

This is the moment when the first real blow or wounding takes place. It signals the start of the actual fighting.

4. Complication

In this phase, neither opponent is winded or badly injured yet, so they are both on top of their game. It may seem as though the opponents are evenly matched, or perhaps that the main character is outmatched. Either way, the reader gets the sense that defeating the bad guy will be a difficult task for the main character.

5. Third Driver (midpoint)

At the midpoint, a serious blow is delivered by one party that establishes them as the superior or dominant fighter.

6. Move to Crisis

Now the fight moves into a more intense stage. The combatant who delivered the serious blow at the midpoint may try to press his/her advantage. The other party must in turn fight harder to try and gain the upper hand. Both parties may acquire some injuries and may be starting to tire. It may seem increasingly obvious in this round who is likely to win.

7. Crisis Driver

At the crisis, there is usually a surprising turn of events. Whoever seemed to be losing the fight suddenly gains the upper hand, possibly by delivering a blow that is more severe than the one they received at the midpoint.

8. Move to Resolution

In the final round, the person who now has the upper hand now presses their advantage, going heavily on the offensive. They want to win before their strength runs out.

Meanwhile, the other person is now "on the ropes." They may experience a growing sense of fear or desperation as they realize they are losing. If it is the main character who is losing, he/she may be looking for some way to escape.

9. Final Driver

If the fight is to have a decisive outcome, this is the moment. Either the winner delivers the final blow to the opponent, which brings the fight to its end, or possibly the loser finds a way to escape before being killed or forced to surrender.

Of course, you won't always write a fight scene to follow this exact pattern. But this is the general model.

As an example, take a look at this formal fight scene from the film, The Way of the Dragon, between Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris. See how many of the nine parts you can spot...

You will note that the structure outlined above works well when applied to fighting with fists or swords, battles with multiple opponents, sports competitions (substitute "wounds" for points scored), or even longer shootouts.

In a pistol duel, there may be only two bullets fired simultaneously at the climax, so the buildup to that moment must be structured in other ways. The drama may be more about one person's effort to avoid a showdown or how the conflict between the two combatants builds to the point where shooting is inevitable.

Other Ways to Add Interest

You'll notice that, when you write a fight scene that is well structured, each of the four stages has a different feel, a different emotional tone, depending on which combatants are winning or losing and their physical state.

Another secret of how to write fight scenes is to add interest by making each stage distinct from the others. For instance, you could...

- Change the combatants. Maybe the hero has to fight different henchmen or underlings before he can face the main opponent in the final stage. Generally, the opponents should get tougher to beat in each stage. (This may be the villain's way of weakening the hero before facing him.)

- Change the weapons. Perhaps the combatants start by fighting with fists, but if one person feels they are losing they may pick up a weapon for the next stage. Or they may start by using guns, but switch to knives or fists when the bullets run out. Medieval knights might start by jousting with lances on horseback, and then switch to fighting on foot with swords. Using different weapons in each stage also lets the characters display different skills.

- Change the terrain. Perhaps they start on level ground, but move onto more difficult or dangerous ground as the fight continues, or especially if one party tries to escape. It's a bit of a cliche to have the final stage of a fight happen on top of a tower or precipice, but it does work to heighten the drama.

How to Write Fight Scenes That are Less Formal

You will note that in fights in real life aren't usually as drawn out as they are in a formal fight. Formal fights usually occur between serious, experienced fighters. But the average person does not have a lot of experience or training in fighting. Also, people in real life can't take as much damage as fictional characters. They usually die, surrender, run away, or pass out after fewer blows.

(Of course, the hero who always kills the bad guy with one shot straight to the heart or brain is also a little unrealistic. In an actual gunfight, a shooter will not likely be so lucky with their first shot. A person may take several minor wounds before being hit in a vital area or bleeding out.)

Real life fighters don't tend to observe the niceties of an aristocratic duel, such as waiting until the opponent is ready before attacking. They may simply attack spontaneously out of anger. They may prefer a quick, intense attack to a prolonged contest.

If your characters are not professional fighters and you are writing in a genre where realism matters, you need to know how to write fight scenes that are more true to life. In that case, you can use the same structure, but modify it so that the actual fight comprises only the middle of the arc...

The Informal Fight Structure

1.Initial Driver

The potential for combat is established, perhaps by something as simple as a character being in the wrong place at the wrong time or accidentally stepping on someone's toes.

2. Setup

The fight may not seem inevitable at first, so the setup may involve more suspense. The scene might begin with one character waiting to ambush another. Or there may be an exchange of words, insults, threats, or efforts to avoid a fight.

3. Second Driver

The fight may begin here, as in the elaborate fight, with the first blow struck.

4. Complication

In this stage, one fighter may seem to have the advantage. If the hero is to win, he will seem to be losing in this round.

5. Third Driver (midpoint)

Here a surprise change of direction occurs in which whoever was losing lands a significant blow on the other that changes the course of the fight.

6. Move to crisis

The fight intensifies. Now the eventual winner presses his/her advantage while the other party is "on the ropes."

7. Crisis

Here the winner delivers a decisive blow (or the loser escapes).

8. Move to Resolution

The fight is over now, so this stage illustrates the aftermath. The combatants may take stock of their injuries and deal with the emotional consequences of the fight.

9. Final Driver

The resolution in this case may be a realization on the part of the main character. Perhaps he has learned something or discovered something in the course of the fight that causes him to pursue a new objective in the next scene. Maybe the fight will cause him to change tactics in pursuing the larger story goal.

Should Sex Stereotypes Affect How You Write Fight Scenes?

Once upon a time, it was rare to see female fighters in stories. Violence was supposed to be men's work and it was considered a sign of bad breeding for a woman to close her fist or strike another person. At the same time, any man who raised a hand against a woman was automatically a villain.

Today, the situation is more complex. It is more common to see female fighters in stories (as well as real life). The ability and willingness to fight is increasingly considered a sign of strength for women the way it traditionally was for men.

This has raised some debate over whether women's traditional disinclination to violence is completely a social construct or if it reflects some biological reality. Some people argue that biological differences between men and women, such as average adrenaline response, means that it takes a lot more provocation for two women to get into a physical exchange than two men -- and longer for women to calm down afterward.

Regardless, the other challenge you may have is how to write fight

a scene between a man and a woman that involves physical violence.

Of course, you could ignore the differences in sex and write the scene the same as you would with any two same-sex characters. However, there are two issues you may need to contend with.

1. Is gender equality in combat completely realistic? It seems to be the case that, on average, men have an advantage in hand-to-hand combat. They tend to have larger bodies. They have a greater ability to build muscle, larger hearts, etc. Are the instances in fiction where women win fights against larger male opponents realistic or merely pandering to the reader? Of course, you are probably not writing about "average" people but about particular characters who may be better or worse fighters than average.

2. Since it is generally considered unfair for someone to beat up on a physically weaker opponent, men tend to be at a moral disadvantge when fighting women.

For instance, if a female character gets into a fistfight

with a male character, is she automatically perceived as the underdog,

and therefore granted the moral high ground?

On the other hand, if a male hero fights a female character, has he automatically forfeited the moral high ground?

Is it a worse loss of moral high ground for a male to strike first vs. a female who strikes first?

None of this may matter if you have a female

hero fighting a male villain. For instance, if a man is verbally rude or

abusive to a woman, and she responds by striking him, many people will

say, "Good for her."

But what if you want to write a fight scene between a male hero and a female villain? If a male hero endures verbal abuse from a female villain, will anyone say, "Good for him" if he responds with physical violence? Probably not, because it is generally considered immoral for a man to hit a woman under any circumstances.

In fact, you might need to take extra steps to keep the reader on the man's side by making the female a bigger threat than the average male villain -- perhaps by making her more ruthless, better trained in violence, etc.

On the other hand, are there scenarios in which a female hero could fight a male villain and lose the moral high ground -- for instance if the woman is young, fit, and well trained and the man is untrained or elderly will the woman be perceived as a bully?

I don't have a definitive answer to these questions, but I do think writers need to consider them.

- Home

- Storytelling Tips

- Writing Fight Scenes